Subtotal: £44.58

Testosterone hormone is the primary male sex hormone, as is androgen in males. In humans, testosterone plays a key role in the development of male reproductive tissues like testicles and prostate. It also promotes secondary sexual characteristics like increased muscle and bone mass and the growth of body hair. It is linked to increased aggression, sex drives, dominance, courtship displays, and a wide range of behavioural characteristics. In addition, this hormone in both sexes is involved in health and well-being. It has a significant effect on overall mood and cognition. It influences social and sexual behaviours. It also impacts metabolism and energy output. Lastly, it affects the cardiovascular system. It also helps in the prevention of osteoporosis. Insufficient levels of hormone in men lead to frailty. Insufficient levels of hormone in men lead to the accumulation of adipose fat tissue within their bodies. Anxiety and depression can also result. Men face sexual performance issues and bone loss.

The testosterone hormone is necessary for normal sperm development. It activates genes in Sertoli cells that promote spermatogonia’s differentiation. It regulates acute HPA (hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis) response under dominance challenge. Androgens enhance muscle growth. This primary hormone also regulates the population of thromboxane A2 receptors on megakaryocytes and platelets and hence platelet aggregation in humans.

Effects are more clearly demonstrable in males than in females but are likely important to both sexes. Some of these effects may decline as testosterone levels decrease in the later decades of adult life.

This sexual differentiation also affects the brain. The enzyme aromatase converts testosterone into oestradiol. This process is responsible for masculinising the brain in male mice. In humans, masculinisation of the foetal brain appears through observation of gender preference. It appears in patients with congenital disorders of androgen formation. It also appears through observation of androgen receptor function. This masculinisation seems associated with functional androgen receptors.

There are some differences between male and female brains that may be due to varying hormone levels. One of the differences is size. The male human brain is, on average, larger.

Health effects of the testosterone hormone

This hormone does not appear to increase the risk of developing prostate cancer. In people who have undergone deprivation therapy, the test increases beyond the castrate level. Studies have demonstrated that these increases accelerate the spread of pre-existing prostate cancer.

The importance of this primary androgen in maintaining cardiovascular health has yielded conflicting results. Nevertheless, maintaining normal testosterone levels in elderly men has been shown to improve many parameters. These parameters are thought to reduce cardiovascular disease risk. They include increased lean body mass, decreased visceral fat mass, decreased total cholesterol, and improved glycaemic control.

High androgen levels are associated with menstrual cycle irregularities in both clinical populations and healthy women. There can also be effects related to unusual hair growth. Other effects include acne, weight gain, and infertility. Occasionally there is even scalp hair loss. Women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) primarily experience these effects. For women with PCOS, hormones like birth control pills can help. They can mitigate the impact of this elevated testosterone level.

Attention, memory, and spatial ability are key cognitive functions affected by testosterone in humans. Preliminary evidence suggests that low testosterone levels may be a risk factor for cognitive decline. It may possibly be a risk factor for dementia of the Alzheimer’s type. This observation is a key argument in life extension medicine. It advocates for the use of testosterone in anti-ageing therapies. Much of the literature, however, suggests a curvilinear or even quadratic relationship between spatial performance and circulating testosterone. Both hypo- and hypersecretion (deficient and excessive secretion) of circulating androgens harm cognition.

Immune system and inflammation

Testosterone hormone deficiency is associated with an increased risk of metabolic syndrome. It is also linked to cardiovascular disease and mortality. These conditions are sequelae of chronic inflammation. Testosterone plasma concentration inversely correlates to multiple biomarkers of inflammation. These include CRP, interleukin 1 beta, interleukin 6, TNF alpha, and endotoxin concentration. It also correlates to leukocyte count. As demonstrated by a meta-analysis, substitution therapy with testosterone results in a significant reduction of inflammatory markers. Different mechanisms act in synergy to mediate these effects. In androgen-deficient men with concomitant autoimmune thyroiditis, substitution therapy with testosterone leads to a decrease in thyroid autoantibody titres. It also results in an increase in the thyroid’s secretory capacity (SPINA-GT).

Medical use

One such medication is testosterone enanthate, which comes in a dosage of 300 mg. Testosterone hormone is used as a medication for the treatment of male hypogonadism, gender dysphoria, and certain types of breast cancer. This type of treatment is known as hormone replacement therapy (HRT) or testosterone replacement therapy (TRT). These therapies maintain serum testosterone levels in the normal range. The decline of testosterone production with age has led to interest in androgen replacement therapy.[55] It is unclear if the use of testosterone for low levels due to ageing is beneficial or harmful.

Testosterone enanthate (300 mg) is included in the World Health Organisation‘s list of essential medicines. These are the most important medications needed in a basic health system. It is available as a generic medication. It can be administered as a cream or transdermal patch that is applied to the skin. It can also be administered by injection into a muscle. Another method is as a tablet that is placed in the cheek. Lastly, it can be administered by ingestion.

Common side effects from testosterone medication include acne, swelling, and breast enlargement in males. Serious side effects may include liver toxicity. They may also include heart disease. A randomised trial found no evidence of major adverse cardiac events compared to placebos in men with low testosterone. Serious side effects may also include behavioural changes. Women and children who are exposed may develop virilisation. It is recommended that individuals with prostate cancer not use the medication. The medication can cause harm if it is used during pregnancy or while breastfeeding.

2020 guidelines from the American College of Physicians support the discussion of testosterone treatment in adult men with age-related low levels of testosterone who have sexual dysfunction. They recommend yearly evaluation regarding possible improvement. If there is none, they recommend discontinuing testosterone. Physicians should consider intramuscular treatments due to costs. The effectiveness and harm of either method are similar to transdermal treatments. <Testosterone treatment not aimed at improving sexual dysfunction may not be recommended.>

No immediate or short-term effects on mood or behaviour were found. The administration of supraphysiologic doses of testosterone for 10 weeks was tested on 43 healthy men.

Behavioural correlations

Sexual arousal

Testosterone levels follow a circadian rhythm that peaks early each day, regardless of sexual activity.

In women, correlations may exist between positive orgasm experience and testosterone levels. Studies have shown small or inconsistent correlations between testosterone levels and male orgasm experience, as well as sexual assertiveness in both sexes.

Sexual arousal and masturbation in women produce small increases in testosterone concentrations. The plasma levels of various steroids significantly increase after masturbation in men, and the testosterone levels correlate to those levels.

Mammalian studies

Studies conducted in rats have indicated that their degree of sexual arousal is sensitive to reductions in testosterone. When testosterone-deprived rats were given medium levels of testosterone, their sexual behaviours (copulation, partner preference, etc.) resumed, but they did not when given low amounts of the same hormone. Therefore, these mammals may provide a model for studying clinical populations among humans with sexual arousal deficits such as hypoactive sexual desire disorder.

Every mammalian species examined demonstrated a marked increase in a male’s testosterone level upon encountering a novel female. The reflexive testosterone increases in male mice are related to the male’s initial level of sexual arousal.

In non-human primates, it may be that testosterone in puberty stimulates sexual arousal. This allows the primate to increasingly seek sexual experiences with females. Thus, it creates a sexual preference for females. Some research has also indicated that if testosterone is eliminated in an adult male human’s or other adult male primate’s system, its sexual motivation decreases, but there is no corresponding decrease in ability to engage in sexual activity (mounting, ejaculating, etc.).

In accordance with sperm competition theory, testosterone levels increase in male rats. This occurs as a response to previously neutral stimuli. The stimuli are conditioned to become sexual in such cases. This reaction engages penile reflexes (such as erection and ejaculation). These reflexes aid in sperm competition when more than one male is present in mating encounters. This allows for more production of successful sperm and a higher chance of reproduction.

Males

In men, higher levels of testosterone are associated with periods of sexual activity.

Men who watch a sexually explicit movie have an average increase of 35% in testosterone, peaking at 60–90 minutes after the end of the film, but no increase is seen in men who watch sexually neutral films. Men who watch sexually explicit films also report increased motivation and competitiveness and decreased exhaustion. A link has also been found between relaxation following sexual arousal and testosterone levels.

Females

Androgens may modulate the physiology of vaginal tissue and contribute to female genital sexual arousal. Women’s level of testosterone is higher when measured pre-intercourse vs. pre-cuddling, as well as post-intercourse vs. post-cuddling. There is a time lag effect when testosterone is administered for genital arousal in women. In addition, a continuous increase in vaginal sexual arousal may result in higher genital sensations and sexually appetitive behaviours.

When females have a higher baseline level of testosterone, they have higher increases in sexual arousal levels. They have smaller increases in testosterone. This evidence indicates a ceiling effect on testosterone levels in females. Sexual thoughts also change the level of testosterone but not the level of cortisol in the female body. Hormonal contraceptives may affect the variation in testosterone response to sexual thoughts.

Testosterone may be an effective treatment in female sexual arousal disorders and is available as a dermal patch. There is no FDA-approved androgen preparation for the treatment of androgen insufficiency. However, it has been used off-label to treat low libido and sexual dysfunction in older women. Testosterone may be a treatment for postmenopausal women as long as they are effectively oestrogenised.

Romantic relationships

Falling in love has been linked with decreases in men’s testosterone levels. Mixed changes are reported for women’s testosterone levels. There has been speculation that these changes in testosterone result in a temporary reduction in differences in behaviour between the sexes. However, relationships seem to maintain the observed testosterone changes over time.

Men who produce less testosterone are more likely to be in a relationship or married. Men who produce more testosterone are more likely to divorce. Marriage or commitment could cause a decrease in testosterone levels. Single men who have not had relationship experience have lower testosterone levels than single men with experience. It is suggested that these single men with prior experience are in a more competitive state than their non-experienced counterparts. Married men who engage in bond-maintenance activities such as spending the day with their spouse or child have no different testosterone levels. This is true compared to times when they do not engage in such activities. Collectively, these results suggest that the presence of competitive activities rather than bond-maintenance activities is more relevant to changes in testosterone levels.

Men who produce more testosterone are more likely to engage in extramarital sex. Testosterone levels do not rely on the physical presence of a partner; testosterone levels of men engaging in same-city and long-distance relationships are similar. Physical presence may be required for women who are in relationships for the testosterone–partner interaction. Same-city partnered women have lower testosterone levels than long-distance partnered women.

Motivation

Testosterone levels play a major role in risk-taking during financial decisions. Higher testosterone levels in men reduce the risk of becoming or staying unemployed. Research has also found that heightened levels of testosterone and cortisol are associated with an increased risk of impulsive and violent criminal behaviour. On the other hand, elevated testosterone in men may increase their generosity, primarily to attract a potential mate.

Aggression and criminality

Most studies support a link between adult criminality and testosterone. Nearly all studies examining the relationship between juvenile delinquency and testosterone have found no significant results. Most studies have found testosterone to be associated with behaviours or personality traits linked with antisocial behaviour and alcoholism. Many studies have been undertaken on the relationship between more general aggressive behaviour and feelings and testosterone. About half of studies have found a relationship, and about half, no relationship. Studies have found that testosterone facilitates aggression by modulating vasopressin receptors in the hypothalamus.

There are two theories on the role of testosterone in aggression and competition. The first is the challenge hypothesis, which states that testosterone would increase during puberty, thus facilitating reproductive and competitive behaviour, which would include aggression. It is therefore the challenge of competition among males that facilitates aggression and violence. Studies conducted have found a direct correlation between testosterone and dominance, especially among the most violent criminals in prison, who had the highest testosterone. The same research found fathers (outside competitive environments) had the lowest testosterone levels compared to other males.

The second theory, which is similar, is referred to as the “evolutionary neuroandrogenic (ENA) theory of male aggression.” Testosterone and other androgens have evolved to masculinise a brain to be competitive, even to the point of risking harm to the person and others. By doing so, individuals with masculinised brains as a result of prenatal and adult life testosterone and androgens enhance their resource-acquiring abilities to survive, attract and copulate with mates as much as possible. The masculinisation of the brain is not just mediated by testosterone levels at the adult stage but also testosterone exposure in the womb. Higher prenatal testosterone, indicated by a low digit ratio, as well as adult testosterone levels, increased the risk of fouls or aggression among male players in a soccer game. Studies have found a correlation between higher prenatal testosterone or a lower digit ratio and higher aggression.

The rise in testosterone during competition predicted aggression in males, but not in females. Subjects who interacted with handguns and an experimental game showed a rise in testosterone and aggression. Natural selection might have evolved males to be more sensitive to competitive and status challenge situations, and the interacting roles of testosterone are the essential ingredient for aggressive behaviour in these situations. Testosterone mediates attraction to cruel and violent cues in men by promoting extended viewing of violent stimuli. Testosterone-specific structural brain characteristics can predict aggressive behaviour in individuals.

The Annual NY Academy of Sciences has found anabolic steroid use (which increases testosterone) to be higher in teenagers, and this was associated with increased violence. Studies have found that administering testosterone increases verbal aggression and anger in some participants.

A few studies indicate that the testosterone derivative oestradiol might play an important role in male aggression. Oestradiol is known to correlate with aggression in male mice. Moreover, the conversion of testosterone to oestradiol regulates male aggression in sparrows during breeding season. Rats who were given anabolic steroids that increase testosterone were also more physically aggressive to provocation as a result of “threat sensitivity”.

The relationship between testosterone and aggression may also function indirectly, as it has been proposed that testosterone does not amplify tendencies towards aggression but rather amplifies whatever tendencies will allow an individual to maintain social status when challenged. In most animals, aggression is the means of maintaining social status. However, humans have multiple ways of obtaining status. If social status rewards pro-social behaviour, these variables could explain why some studies have found a correlation between testosterone and pro-social behaviour. Therefore, the association between testosterone and aggression and violence stems from the reward of social status for these behaviours. The relationship might work like this: testosterone can increase aggression, but only to keep it at a normal level; if a person is chemically or physically castrated, their aggression will go down (but not completely disappear), and they only need a small amount of testosterone before castration to bring their aggression back to normal, which will stay the same even if they obtain more testosterone later. Testosterone may also simply exaggerate or amplify existing aggression; for example, chimpanzees who receive testosterone increases become more aggressive to chimps lower than them in the social hierarchy but will still be submissive to chimps higher than them. Testosterone thus does not make the chimpanzee indiscriminately aggressive but instead amplifies his pre-existing aggression towards lower-ranked chimps.

In humans, testosterone appears more to promote status-seeking and social dominance than simply increasing physical aggression. When controlling for the effects of belief in having received testosterone, women who have received it make fairer offers than women who have not received it.

Fairness

Testosterone might encourage fair behaviour. For one study, subjects took part in a behavioural experiment where the distribution of a real amount of money was decided. The rules allowed both fair and unfair offers. The negotiating partner could subsequently accept or decline the offer. The fairer the offer, the less probable a refusal by the negotiating partner. If no agreement was reached, neither party earned anything. Test subjects with an artificially enhanced testosterone level generally made better, fairer offers than those who received placebos, thus reducing the risk of rejection to a minimum. Two later studies have empirically confirmed these results. However, men with high testosterone were significantly 27% less generous in an ultimatum game.

Biological activity

Free testosterone

Lipophilic hormones, such as steroid hormones including testosterone, are transported through specific and non-specific proteins in water-based blood plasma. Specific proteins include sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), which binds testosterone, dihydrotestosterone, oestradiol, and other sex steroids. Nonspecific binding proteins include albumin. The free part is the portion of the total hormone concentration that is not bound to its specific carrier protein. As a result, testosterone that is not bound to SHBG is called free testosterone. Only the free amount of testosterone can bind to an androgenic receptor, which means it has biological activity. Most testosterone is attached to SHBG, but a small amount (1%-2%) is attached to albumin, and this attachment is weak and can easily change; therefore, both albumin-bound and free testosterone are considered usable testosterone. This binding plays an important role in regulating the transport, tissue delivery, bioactivity, and metabolism of testosterone. At the tissue level, testosterone dissociates from albumin and quickly diffuses into the tissues. The percentage of testosterone bound to SHBG is lower in men than in women. Both the free testosterone and the testosterone attached to albumin can be used by the tissues (together they make up the bioavailable testosterone), while SHBG blocks the effects of testosterone in a strong and permanent way. The relationship between sex steroids and SHBG in physiological and pathological conditions is complex, as various factors may influence the levels of plasma SHBG, affecting the bioavailability of testosterone.

Steroid hormone activity

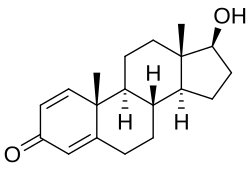

The effects of testosterone in humans and other vertebrates occur by way of multiple mechanisms: by activation of the androgen receptor (directly or as dihydrotestosterone) and by conversion to oestradiol and activation of certain oestrogen receptors. Androgens such as testosterone have also been found to bind to and activate membrane androgen receptors.

Free testosterone (T) is transported into the cytoplasm of target tissue cells, where it can bind to the androgen receptor or be reduced to 5α-dihydrotestosterone (5α-DHT) by the cytoplasmic enzyme 5α-reductase. 5α-DHT binds to the same androgen receptor even more strongly than testosterone, so its androgenic potency is about five times that of T. The T-receptor or DHT-receptor complex undergoes a structural change that allows it to move into the cell nucleus and bind directly to specific nucleotide sequences of the chromosomal DNA. The areas of binding are called hormone response elements (HREs) and influence transcriptional activity of certain genes, producing the androgen effects.

Androgen receptors occur in many different tissues of vertebrate body systems, and both males and females respond similarly to similar levels. Greatly differing amounts of testosterone prenatally, at puberty, and throughout life account for a share of biological differences between males and females.

The bones and the brain are two important tissues in humans where the primary effect of testosterone is by way of aromatisation to oestradiol. In the bones, oestradiol accelerates ossification of cartilage into bone, leading to closure of the epiphyses and conclusion of growth. In the central nervous system, testosterone is aromatised to oestradiol. Oestradiol rather than testosterone serves as the most important feedback signal to the hypothalamus (especially affecting LH secretion). In many mammals, prenatal or perinatal “masculinisation” of the sexually dimorphic areas of the brain by oestradiol derived from testosterone programmes later male sexual behaviour.

Biochemistry

Biosynthesis

Like other steroid hormones, testosterone is derived from cholesterol. The first step in the biosynthesis involves the oxidative cleavage of the side chain of cholesterol by cholesterol side-chain cleavage enzyme (P450scc, CYP11A1), a mitochondrial cytochrome P450 oxidase, with the loss of six carbon atoms to give pregnenolone. In the next step, two additional carbon atoms are removed by the CYP17A1 (17α-hydroxylase/17,20-lyase) enzyme in the endoplasmic reticulum to yield various C19 steroids. In addition, the 3β-hydroxyl group is oxidised by 3-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase to produce androstenedione. In the final and rate-limiting step, the C17 keto group androstenedione is reduced by 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase to yield testosterone.

The largest amounts of testosterone (>95%) are produced by the testes in men, while the adrenal glands account for most of the remainder. Testosterone is also synthesised in far smaller total quantities in women by the adrenal glands, thecal cells of the ovaries, and, during pregnancy, by the placenta. In the testes, testosterone is produced by the Leydig cells. The male generative glands also contain Sertoli cells, which require testosterone for spermatogenesis. Like most hormones, testosterone is supplied to target tissues in the blood, where much of it is transported bound to a specific plasma protein, sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG).

Regulation

In males, testosterone is synthesised primarily in Leydig cells. The number of Leydig cells in turn is regulated by luteinising hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). In addition, the amount of testosterone produced by existing Leydig cells is under the control of LH, which regulates the expression of 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase.

The amount of testosterone synthesised is regulated by the hypothalamic–pituitary–testicular axis. When testosterone levels are low, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) is released by the hypothalamus, which in turn stimulates the pituitary gland to release FSH and LH. These latter two hormones stimulate the testis to synthesise testosterone. Finally, increasing levels of testosterone create a negative feedback loop that acts on both the hypothalamus and pituitary gland to inhibit the release of GnRH and FSH/LH, respectively.

Factors affecting testosterone levels may include:

-

- Age: Testosterone levels gradually reduce as men age. This effect is sometimes referred to as andropause or late-onset hypogonadism.

-

- Exercise: Resistance training increases testosterone levels acutely; however, in older men, that increase can be avoided by protein ingestion. Men who engage in endurance training may experience a decrease in their testosterone levels.

-

- Nutrients: Vitamin A deficiency may lead to suboptimal plasma testosterone levels. The secosteroid vitamin D in levels of 400–1000 IU/d (10–25 μg/d) raises testosterone levels. Zinc deficiency lowers testosterone levels, but over-supplementation has no effect on serum testosterone. There is limited evidence that low-fat diets may reduce total and free testosterone levels in men.

-

- Weight loss: Reduction in weight may result in an increase in testosterone levels. Fat cells synthesise the enzyme aromatase, which converts testosterone, the male sex hormone, into oestradiol, the female sex hormone. However, no clear association between body mass index and testosterone levels has been found.

-

- Miscellaneous: Sleep (REM sleep) increases nocturnal testosterone levels.

-

- Behaviour: Dominance challenges can, in some cases, stimulate increased testosterone release in men.

-

- Foods: Natural or man-made antiandrogens, including spearmint tea, reduce testosterone levels. Liquorice can decrease the production of testosterone, and this effect is greater in females.

Distribution

The plasma protein binding of testosterone is 98.0 to 98.5%, with 1.5 to 2.0% free or unbound. It is 65% bound to sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) and 33% bound weakly to albumin.

Metabolism

Both testosterone and 5α-DHT are metabolised mainly in the liver. Approximately 50% of testosterone is metabolised via conjugation into testosterone glucuronide and, to a lesser extent, testosterone sulphate by glucuronosyltransferases and sulfotransferases, respectively. An additional 40% of testosterone is metabolised in equal proportions into the 17-ketosteroids androsterone and etiocholanolone via the combined actions of 5α- and 5β-reductases, 3α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, and 17β-HSD, in that order. Androsterone and etiocholanolone are then glucuronidated and, to a lesser extent, sulfated similarly to testosterone. The conjugates of testosterone and its hepatic metabolites are released from the liver into circulation and excreted in the urine and bile. Only a small fraction (2%) of testosterone is excreted unchanged in the urine.

In the hepatic 17-ketosteroid pathway of testosterone metabolism, testosterone is converted in the liver by 5α-reductase and 5β-reductase into 5α-DHT and the inactive 5β-DHT, respectively. Then, 5α-DHT and 5β-DHT are converted by 3α-HSD into 3α-androstanediol and 3α-etiocholanediol, respectively. Subsequently, 3α-androstanediol and 3α-etiocholanediol are converted by 17β-HSD into androsterone and etiocholanolone, which is followed by their conjugation and excretion. 3β-Androstanediol and 3β-etiocholanediol can also be formed in this pathway when 5α-DHT and 5β-DHT are acted upon by 3β-HSD instead of 3α-HSD, respectively, and they can then be transformed into epiandrosterone and epietiocholanolone, respectively. A small portion of approximately 3% of testosterone is reversibly converted in the liver into androstenedione by 17β-HSD.

In addition to conjugation and the 17-ketosteroid pathway, testosterone can also be hydroxylated and oxidised in the liver by cytochrome P450 enzymes, including CYP3A4, CYP3A5, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, and CYP2D6. 6β-Hydroxylation and, to a lesser extent, 16β-hydroxylation are the major transformations. The 6β-hydroxylation of testosterone is catalysed mainly by CYP3A4 and to a lesser extent CYP3A5 and is responsible for 75 to 80% of cytochrome P450-mediated testosterone metabolism. In addition to 6β- and 16β-hydroxytestosterone, 1β-, 2α/β-, 11β-, and 15β-hydroxytestosterone are also formed as minor metabolites. Certain cytochrome P450 enzymes, such as CYP2C9 and CYP2C19, can also oxidise testosterone at the C17 position to form androstenedione.

Two of the immediate metabolites of testosterone, 5α-DHT and oestradiol, are biologically important and can be formed both in the liver and in extrahepatic tissues. Approximately 5 to 7% of testosterone is converted by 5α-reductase into 5α-DHT, with circulating levels of 5α-DHT about 10% of those of testosterone, and approximately 0.3% of testosterone is converted into oestradiol by aromatase. 5α-Reductase is highly expressed in the male reproductive organs (including the prostate gland, seminal vesicles, and epididymides), skin, hair follicles, and brain, and aromatase is highly expressed in adipose tissue, bone, and the brain. As much as 90% of testosterone is converted into 5α-DHT in so-called androgenic tissues with high 5α-reductase expression, and due to the several-fold greater potency of 5α-DHT as an AR agonist relative to testosterone, it has been estimated that the effects of testosterone are potentiated 2- to 3-fold in such tissues.

Levels

Total levels of testosterone in the body have been reported as 264 to 916 ng/dL (nanograms per decilitre) in non-obese European and American men aged 19 to 39 years, while mean testosterone levels in adult men have been reported as 630 ng/dL. Although this range is commonly used as a reference, some physicians have disputed its use to determine hypogonadism. Several professional medical groups have recommended that 350 ng/dL generally be considered the minimum normal level, which is consistent with previous findings. Levels of testosterone in men decline with age. In women, mean levels of total testosterone have been reported to be 32.6 ng/dL. In women with hyperandrogenism, mean levels of total testosterone have been reported to be 62.1 ng/dL.

Measurement

When measuring testosterone in blood samples, different assay techniques can yield different results. Immunofluorescence assays exhibit considerable variability in quantifying testosterone concentrations in blood samples due to the cross-reaction of structurally similar steroids, leading to overestimating the results. In contrast, the liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry method is more desirable: it offers superior specificity and precision, making it a more suitable choice for this application.

Testosterone’s bioavailable concentration is commonly determined using the Vermeulen calculation or, more precisely, using the modified Vermeulen method, which considers the dimeric form of sex hormone-binding globulin.

Both methods use chemical equilibrium to derive the concentration of bioavailable testosterone: in circulation, testosterone has two major binding partners, albumin (weakly bound) and sex hormone-binding globulin (strongly bound). These methods are described in detail in the accompanying figure.

-

- Dimeric sex hormone-binding globulin with its testosterone ligands

-

- Two methods for determining the concentration of bioavailable testosterone

Testosterone as Medication

Testosterone (T) is a medication and naturally occurring steroid hormone. It is used to treat male hypogonadism, gender dysphoria, and certain types of breast cancer. It may also be used to increase athletic ability in the form of doping. It is unclear if the use of testosterone for low levels due to ageing is beneficial or harmful. Testosterone can be used as a gel or transdermal patch that is applied to the skin topically, intramuscularly (IM), buccally (a tablet dissolved between the gum and cheek inside the mouth), or as an oral tablet (tablet swallowed by mouth).

Common side effects of testosterone include acne, swelling, and breast enlargement in men. Serious side effects may include liver toxicity, heart disease, and behavioural changes. Women and children who are exposed may develop masculinity. It is recommended that individuals with prostate cancer should not use the medication. It can cause harm to the baby if used during pregnancy or breastfeeding. Testosterone is in the androgen family of medications.

Testosterone was first isolated in 1935 and approved for medical use in 1939. Between 2001 and 2011, the United States saw a threefold increase in use rates. It is on the World Health Organisation’s List of Essential Medicines. It is available as a generic medication. In 2021, it was the 143rd most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 4 million prescriptions.

Medical uses

The primary use of testosterone is the treatment of males with too little or no natural testosterone production, also termed male hypogonadism or hypoandrogenism (androgen deficiency). This treatment is referred to as hormone replacement therapy (HRT), or alternatively, and more specifically, as testosterone replacement therapy (TRT) or androgen replacement therapy (ART). It is used to maintain serum testosterone levels in the normal male range. The decline of testosterone production with age has led to interest in testosterone supplementation.

The most common medication used in TRT is testosterone enanthate 300 mg. There are smaller doses like 200 mg or 250 mg.

A 2020 guideline from the American College of Physicians supports the discussion of testosterone in adult men with age-related low levels of testosterone who have sexual dysfunction. They recommend yearly evaluation regarding possible improvement and, if none, to discontinue testosterone; physicians should consider intramuscular treatments rather than transdermal treatments due to costs and since the effectiveness and harm of either method are similar. Doctors may not recommend testosterone treatment for reasons other than the potential improvement of sexual dysfunction.

Signs of low testosterone in men

Testosterone deficiency (also termed ‘hypotestosteronism’ or ‘hypotestosteronemia’) is an abnormally low testosterone production. It may occur because of testicular dysfunction (primary hypogonadism) or hypothalamic–pituitary dysfunction (secondary hypogonadism) and may be congenital or acquired.

If you are looking for any product from testosterone steroids, browse our selection below.

Testosterone

-

£28.00

£31.02PROPER LABS – Proper Sust 250

-

-

-